The Herald

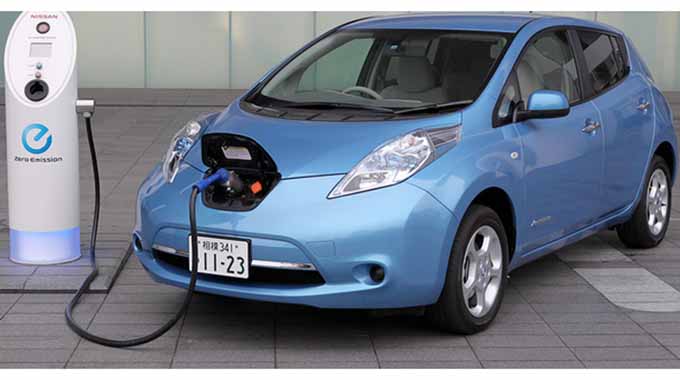

One of the major global initiatives to combat climate change is the rapid switchover to electric cars, with many major producing countries targeting between 2030 and 2035 as the year when all new cars will be electric, and while that may be ambitious, the slippage is unlikely to be more than a few years.

And in any case it is likely that high percentages of new vehicles will be electric by the target date even if the switch-over is not complete.

This is good news for Zimbabwe. Electric cars need batteries, big batteries weighing about half a ton and the most efficient batteries for powering cars are composed of thousands of lithium-ion cells containing more than 60kg of lithium carbonate between them or 8kg to 12kg of pure lithium metal although this metal is always in the form of a salt since the metal is so reactive.

A fleet of around 1.5 billion vehicles, roughly the size of the present global vehicle fleet and that is growing as vehicle ownership grows almost in developing countries will need up to 20 million tonnes of lithium for the batteries, and while in future old batteries will be recycled, with lithium probably a by-product of the recycling for the expensive nickel and cobalt cathode metals, demand will obviously remain very high.

Alternatives are being developed, using lithium hydroxide, but again lithium ions are the core of the electrolytic process and so lithium is needed.

And this is even better news for Zimbabwe since it is easier to use solid lithium ores than the brine deposits that have been a major source to produce that lithium salt. Zimbabwe’s deposits are solid ores.

This helps explain why Australian mining companies have been so keen on investing in Zimbabwe. Australia is a major producer of lithium using ore bodies and its companies have built up the expertise for viable mining; now they are expanding out of Australia and Zimbabwe has been a targeted source, especially once the Second Republic sorted out our investment policies making it easy, let alone possible, to invest and introducing the policy that an investor can have the rights to enough ore body to make the investment viable.

After the initial prospecting and proving of the Arcadia ore deposit by a company that specializes in the prospecting side, a major production company, Prospect Resources, was brought in so serious mining could start.

This is normal; the specialist prospecting firms establish the value of a find and then sell out to the actual major miner.

Prospect has not just been sitting on Arcadia. It has been looking around and has found another similar ore body nearby to extend its reserves. There are other sources of lithium, so Zimbabwe has to remain attractive for investment.

The Democratic Republic of Congo has a huge ore body and while this is expected to be exploited in the near future it is in the middle of the country so logistics need to be upgraded.

There is a collection of huge brine deposits in South America, roughly where Chile, Argentina and Bolivia meet and all three countries are looking for more investment. Processing brine is not exactly an instant process.

Once pumped to the surface and the required salts precipitated, and that requires a major input of other minerals, it takes two years of solar drying before the lithium salts are a solid.

The Americans are looking at mining deposits in North Carolina, again involved with an Australian company, and at brine and dried brine deposits in California.

China probably has the largest deposits and so it is likely that country will be self sufficient despite having the largest motor manufacturing sector in the world. Almost everybody else will need to import.

The general consensus is that while world reserves are more than adequate for an electrified vehicle fleet and to provide the lithium batteries for solar and wind installations, prices are likely to go higher although not nearly as high as to make extraction from sea water anything close to viable.

So again Zimbabwe wins and this growing demand makes prospecting for new deposits and attracting further investment important.

Just producing a couple of percent of the growing global demand, and we could do a lot better, will create a lot of jobs and a lot of wealth and while investors will take a modest slice in dividends most of the money remains in Zimbabwe.

Should the lithium production be large enough it will become viable not just to process the lithium ores the miners dig up into the required lithium salts for the battery trade, and that benefit is already basically locked in since transporting ore is an expensive business, but to start making the batteries themselves.

Most of the other metals needed, with nickel being the major one, are already mined in Zimbabwe.

But investment in a battery factory requires, as in so many industrial processes, adequate volumes before viability is ensured and that in turn means we must have adequate output of the pure lithium salts to keep a large factory busy.

In many ways this global switch to the electric car makes lithium probably more important that any petroleum condensate finds at Muzarabani, although the gas finds will be crucial in enabling Zimbabwe to generate enough electricity to keep the batteries in our own growing electric fleet fully charged.

That switch to electric vehicles will make lithium and electricity the two vital products we can use to not just cope with the switch, but to make some decent money from the change.

Lithium is obvious, but being able to sell peak power to neighbours, so they can charge their own cars when power supplies are tight, could be very profitable.

Load shedding is the last thing you need when you want to charge your car and with a lot of hydro and gas power, even if we use coal for base load, we can supply peak power on demand and charge the premium it attracts.

In fact the change over to the green global economy will probably allow a resource-rich country like Zimbabwe to emerge on the winning side, economically, and we need to ensure we factor in the green economy into our technical and development strategies, working out what the world needs and then seeing what we can find and supply.

Since a lot of the development work requires a few years to move from prospecting to product it appears we need to start now thinking hard how we can make money from the global commitments to the new economies and then put in the measures that we need to make that money.