Source: Unsplash / Michael Fousert

Australia’s top economists overwhelmingly support government measures to accelerate the transition to electric cars in order to meet emissions reduction targets.

An exclusive survey of 62 eminent Australian economists – chosen by their peers – found 51 measures to encourage the diffusion of electric cars, including subsidizing public charging stations, subsidizing the purchase of all-electric vehicles and setting a date for banning imports of traditional cars.

Only eleven are against such measures, three of them because they prefer a CO2 tax.

Six of the 51 who supported special measures said they were reluctant to do so, as their preferred alternative would be a carbon price or tax rather than subsidizing “one of the many alternative to reduce emissions”.

Cars make up about half of Australia’s traffic emissions, which makes up about 8% of Australia’s total emissions.

But the spread of electric vehicles in Australia is dwarfed by the rest of the world.

For one, all-electric cars accounted for just 0.7% of new car sales in Australia in 2020, compared with 5% in China and 3.5% in the European Union.

Australia has no domestic auto industry to protect, which means industrial policy concerns don’t need to halt the transition.

Norway plans to ban sales of new gasoline cars from 2025; Denmark, the Netherlands, Ireland and Israel from 2030; and California and the UK from 2035.

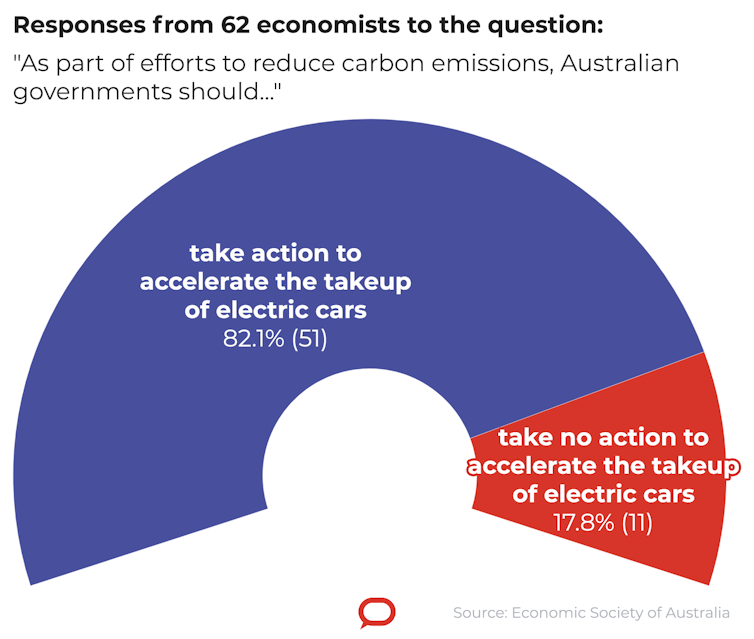

When asked if Australia should take action to accelerate the transition, eight out of ten of the 62 economists selected by the Economic Society said so.

Economic Society of Australia / The Conversation, CC BY-ND

The results represent a departure into a profession whose usual advice is not to disturb the markets.

One participant, Professor Gigi Foster of the University of NSW, said an important question needed to be answered to justify government intervention: “What is the market failure here?”

The market failure was pollution, which placed a cost on the community beyond the drivers of conventionally powered cars, and the planet in raising global temperatures.

Broad support: grants for charging points

Without dealing with a carbon price, measures that accelerate the switch to electric vehicles could have a similar effect.

By far the most popular measure, out of six presented to the panelists who supported government measures, was subsidizing public charging points, which was supported by 84%.

The second most popular was the elimination of the luxury car tax on all-electric vehicles. Currently, the 35% tax applies to cars valued at more than $ 69,152 and $ 79,659 to fuel efficient vehicles.

Around 43% supported the mandatory introduction of charging points in new homes and new parking spaces, while 39% supported setting a date for a ban on imports of petrol and diesel vehicles.

Matthew Butlin, chairman of South Australia’s Productivity Commission, noted that much of Australia is non-urban and unlikely to have charging points for some time.

Without government action to expedite the installation of remote charging stations, many buyers would be reluctant to drive electric, even if they mostly drive in cities.

If they were in place, there would be good reasons to ban imports of gasoline and diesel vehicles, but only then.

Others wanted to postpone the import ban on conventionally powered cars until Australia had a lower-emission electricity mix.

Lisa Magnani, a professor at Macquarie University, said electric vehicles cause significant emissions as three-quarters of Australia’s electricity is generated from coal.

Danielle Wood, executive director of the Grattan Institute, disagreed, saying “network effects” are an argument for an early switch.

Network effects build on themselves

The more people switch, the more charging stations would be built and the prices of electric cars would fall, causing more people to switch and increasing the benefits of decarbonising the electricity supply.

The sooner Australia switched, the easier it would be to achieve net zero emissions by 2050 without the need for a cash for clunkers scheme to buy back polluting vehicles.

Setting 2035 as the date for the gasoline-powered car import ban, as recommended this year by the International Energy Agency, would give buyers time to adjust as the charging infrastructure evolves.

Tax expert John Freebairn said electric cars have already been heavily subsidized by evading the fuel consumption tax that has been used to finance roads, despite efforts by some states to fill the void.

Sydney University economist Stefanie Schurer, on the other hand, argued that bulky and polluting sport utility vehicles would be effectively subsidized because of the tax benefits they received at work.

Former Liberal Party leader John Hewson of the Crawford School of Public Policy said there was an urgent need to smooth the transition.

Smooth transition to electric cars now “urgent”

It was only ten years from 1903 to 1913 for the United States to switch from horse-powered to gasoline-powered vehicles, and the technology was adopted faster today, particularly in Australia.

Other economists surveyed found that, besides electrical installation, there is still a lot that could be done to reduce harmful emissions.

Sue Richardson said Australia should seriously limit its tailpipe emissions from new cars. Australia is unusual among developed nations in that it does not have such a border, making it a preferred market for high-emission cars.

Rana Roy said a better approach would be to limit transportation itself through remote working and efforts to encourage walking and cycling. Electric car subsidies could repel such movements.

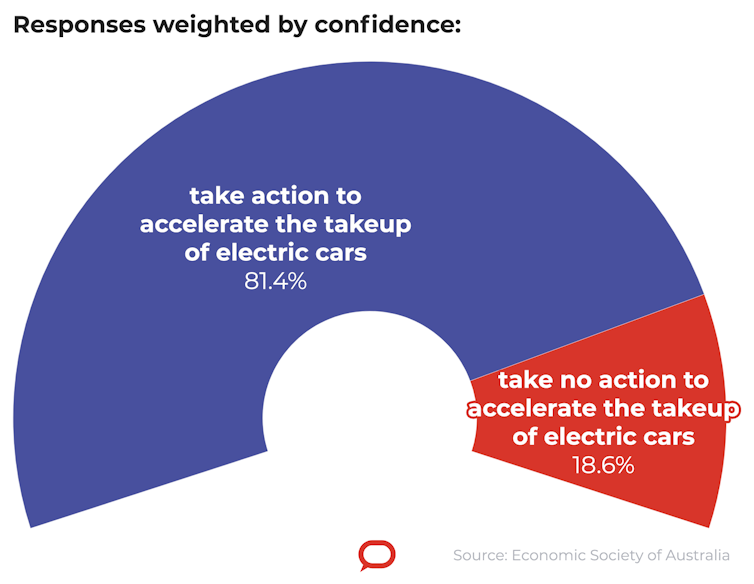

When the responses to the survey were weighted on a scale of 1 to 10 based on respondents’ trust, support for specific measures to encourage transition remained about the same, which was supported by eight in ten of the economists surveyed.

Economic Society of Australia / The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Detailed answers:

![]()

This article was republished by The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.